React with TypeScript

TypeScript is a superset of JavaScript which primarily provides optional static typing, classes, and interfaces.

Why use TypeScript

Easy to read and understand components

Type Checking at compile time is way better than things crashing-or-worse-behaving unexpectedly at run time.

You get a better development experience because autocomplete knows more about what you'r intending on doing.

Large codebase stays more maintainable because you're able to put guardrails on how your code can be used.

The Fundamentals

Basics

const User = () => {return (<main><h1>Hello</h1><p>My Name Is [NAME_HERE]</p></main>);};const Application = () => <User />;export default Application;

Above, we can see a fairly simple User component. As it stands right now, it doesn't take any props or hold onto any state. For our purposes, it might as well just be some static HTML. It really doesn't even need to be React.

Is this JavaScript or TypeScript? The answer is Out of the box, TypeScript is going to try to do everything in its power to infer all of the types for you.

This is a simple, but core concept that we're going to playing with during our time together. TypeScript is trying its hardest to stay out of your way. Occasionally, we need to step in a give it some hints about what we're intending to do. If you find yourself fighting with TypeScript—then it's worth taking a step back and considering your approach.

Looking at the component in this example. TypeScript has figured out that User, in this case, is a function that takes no arguments and returns a JSX.Element , which is a type it knows about from React.

const User: () => JSX.Element;

Refactoring from PropTypes

In JavaScript, we've traditionally used React.PropTypes in order to make sure that we were passing

the correct types to our React components. React.PropTypes would only run at run-time and in

development and would spit out console warnings in the event that the component received the wrong types. This was good, but we can do better with TypeScript—specifically, we can do this statically and at compile time.

Let's take a look at how this might look in JavaScript.

import * as PropTypes from "prop-types";const User = ({ name }) => <h1>Welcome, {name}!</h1>;User.propTypes = {name: PropTypes.string,};

There is no need for PropTypes in TypeScript as that's pretty much a large part of what TypeScript does on our behalf.

type UserProps = { name: string };const User = ({ name }: UserProps) => <h1>Welcome, {name}!</h1>;

TypeScript has now created the following type for this component:

const User: ({ name }: UserProps) => JSX.Element;

Inline Type Declarations

An aside: You could also do this inline if it makes you happier. But, it shouldn't make you happier, because it's one of those things that will get out of control fairly quickly.

const User = ({ name }: { name: string }) => <h1>Welcome, {name}!</h1>;

This is fine for one prop, but it doesn't scale particularly well. If the number of curly braces is intimidating to you, let's think about what this looks like without all of the destructuring in place.

type UserProps = { name: string };const User = (props: UserProps) => <h1>Welcome, {props.name}!</h1>;

This is not dissimilar from if we did something simple, like this:

const addTwo = (n: number) => n + 2;

We're just annotating our functions with some extra information to tell TypeScript what we're intending.

Commonly-Used Props

Let's take a moment to look at some of the types that go along with some of the more common props that we tend to see in React applications.

For starters, we have our basic primitives.

type User = {email: string;age: string;isMarried: boolean;};

We can also have arrays or collections of primitives.

type User = {hobbies: string[];};

Sometimes, we don't want to allow any string—only certain strings. We can use a union type to represent this.

type User = {hobbies: string[];status: "loading" | "error" | "success";};

It's not uncommon for us to find ourselves using objects in JavaScript (erm, TypeScript). So, what would that look like?

type User = {login: {}; // Can have any properties and values.name: {title: string;first: string;last: string;};location: {city: string;state: string;country: string;}[]; // An array of objects of a certain shape.};

We could refactor this a bit. (I know, it's a contrived example, but go along with it.)

type Name = {title: string;first: string;last: string;};type Location = {city: string;state: string;country: string;};type User = {name: Name;location: Location;};

So, if you look at our two object examples above, we're missing something.

{}will allow for an object with any keys and any values.{ title: string; first: string; last: string; }will only allow for an object with three keys:title,first- and

lastas long as those values are strings.

But, what if we wanted to find a happy medium? What if we wanted a situation where we said, "Listen, the key can be any string and the value has to be of a certain type.

That might look something like this:

type ItemHash = {[key: string]: Item;};

Or, if we wanted to say the keys are number and the values are strings, it would look like this:

type Dictionary = {[key: number]: string;};

Another way of writing either of those would be as follows:

Record<string, Item>Record<number, string>

I prefer the first syntax, personally. But, this is your life. You do what you want.

Okay, so we tend to also pass functions around, right? What does that look like?

type UserProps = {// Does not take any arguments. Does not return anything.onHover: () => void;// Takes a number. Returns nothing (e.g. undefined).onChange: (id: number) => void;// Takes an event that is based on clicking on a button.// Returns nothing.onClick(event: React.MouseEvent<HTMLButtonElement>): void;};

A standalone function that you type as your declare it, is a little bit different.

const add = (a: number, b: number): number => {return a + b;};function subtract(a: number, b: number): number {return a - b;}

Finally, we should consider the fact that not every prop is required.

type UserProps = {requiredProp: boolean;optionalProp?: string;};

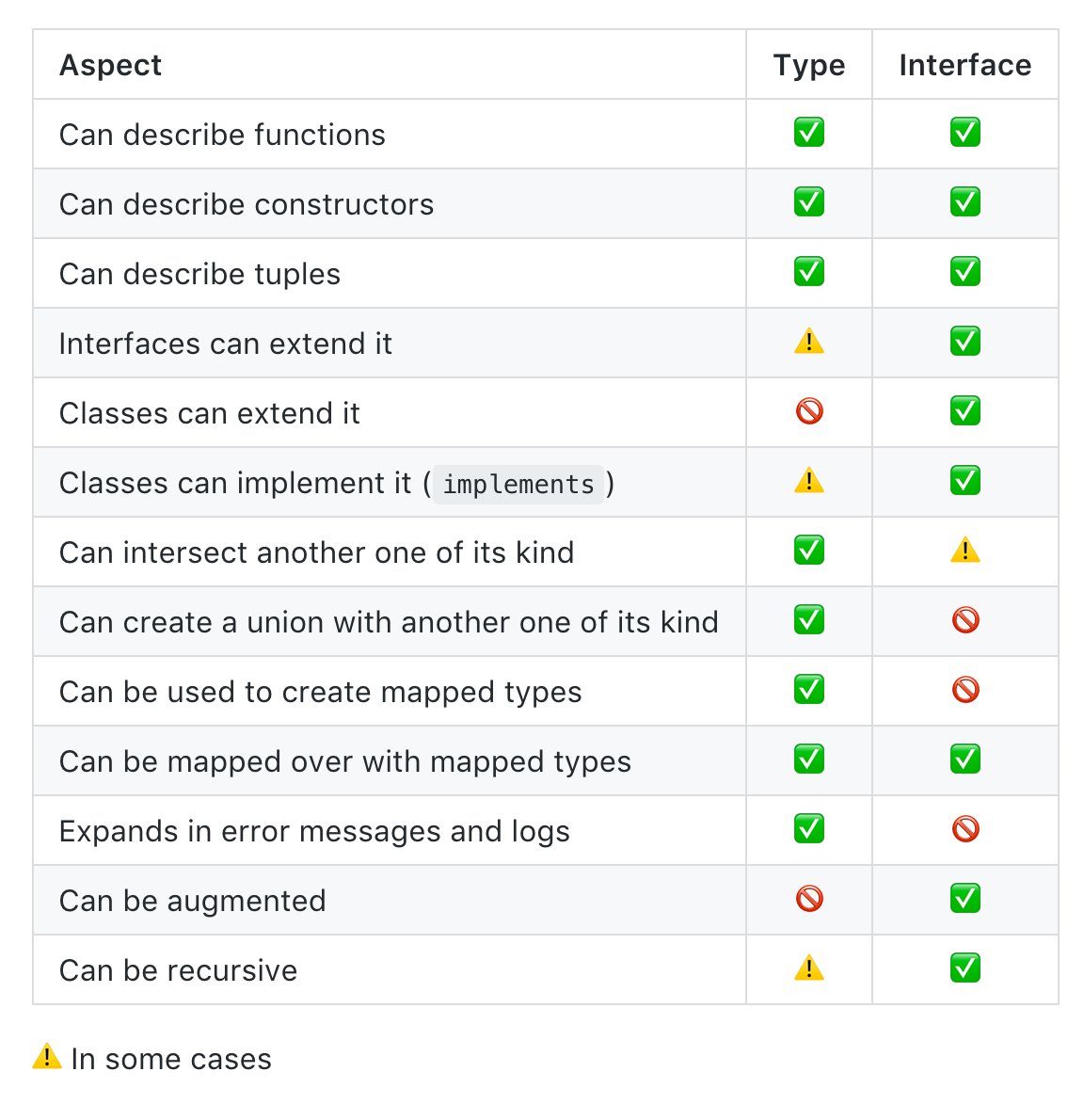

Types Versus Interfaces

The short answer: By and large, it doesn't really matter. (But, that answer probably isn't good enough for your curiosity, is it?)

Interfacesare commonly used for defining the shape of objects and classes.- You might however just want to define a

typeof function or atypealias,typesare cool too.

From Microsoft's TypeScript Handbook:

Type aliases and interfaces are very similar, and in many cases you can choose between them freely. Almost all features of an interface are available in type, the key distinction is that a type cannot be re-opened to add new properties vs an interface which is always extendable.

- Use

interfacesfor public APIs since the consumer can then extend them if needed. - Consider using

typefor your React Component Props and State, for consistency and because it is more constrained.

TL; DR you can extend interfaces. This is convenient, bit it can also make things more complicated. It's up to you to decide if this is a think that makes your life better or not.

Here is a fun chart to look at.

you can adopt a simple strategy: use interfaces to describe objects, use types for everything else.

Typing Children

I don't want to ruin the surprise for you, but if all the code we write was solely about just strings and numbers, we'd be spending very little time together. Things can get a little bit tricky when we want to use TypeScript to specify non-primitive types—namely other React components.

type BoxProps = { children: any };const Box = ({ children }: BoxProps) => {return (<section style={{ padding: "1em", border: "5px solid purple" }}>{children}</section>);};export default function Application() {return (<Box>Just a string.<p>Some HTML that is not nested.</p><Box><h2>Another React component with one child.</h2></Box><Box><h2>A nested React component with two children.</h2><p>The second child.</p></Box></Box>);}

As it stands in the above code, children has the type of any, which is basically an opt-out of every

that TypeScript has to offer you. This isn't great.

so if take a close look at the code you will find

Boxrenderschildren.- It can render more than one child.

- That child can be another React component.

- That child can be a standard HTML element.

But, what can we use to specify that a given prop should be another React component?

Off the top of my head, here are some things that you could try.

JSX.ElementJSX.Element[]JSX.Element | JSX.Element[]React.ReactNodeReact.ReactChildrenReact.ReactChild[]

Why don't you take it for a spin and see what works best for you? in the next sandbox 😉

Solution

How do we type this? Well. We have a few choices.

JSX.Element;: 💩 This doesn't account for arrays at all.JSX.Element | JSX.Element[];😕 This doesn't accept strings.React.ReactChildren;: 🤪 Not at even an appropriate type; it's a utility function.React.ReactChild[];: 😀 Accepts multiple children, but it doesn't accept a single child.React.ReactNode;: 🏆 Accepts everything.

I know now you'r thinking what's the hell is JSX.Element and ReactNOde, keep calm and read this

Typing Styling

What if we wanted to make the box a little bit more customizable?

We'll explore the following:

- How to type CSS properties.

- How to use an optional type.

import "./styles.css";import * as React from "react";+ type BoxProps = { children: React.ReactNode; style?: React.CSSProperties };const Box = ({ children, style = {} }: BoxProps) => {return (+ <section style={{ padding: "1em", border: "5px solid purple", ...style }}>{children}</section>);};export default function Application() {return (<Box>Just a string.<p>Some HTML that is not nested.</p>+ <Box style={{ borderColor: "red" }}><h2>Another React component with one child.</h2></Box><Box><h2>A nested React component with two children.</h2><p>The second child.</p></Box></Box>);}